Курдские племена,кланы,роды.

Kurdish Language

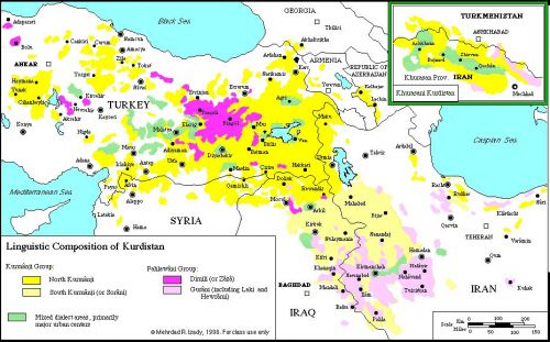

www.kurdist.ru Kurdish (Kurdish: Kurdí, كوردی, Kurdî, Кöрди) language belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. Kurdish dialects are members of the northwestern subdivision of the Indo-Iranic language, Iranic branch of this largest family of language in the world. The Kurdish language is an independent language, having its own historical development, continuity, grammatical system and rich living vocabularies. The Kurdish language was derived from the ancient "Median" language or "Proto-Kurdish". Ca. 30 million people in the high land of Middle East, Kurdistan, speak different dialect of Kurdish.

Kurdish dialects

Kurdish dialects are dialects of the Kurdish language. They are linguistic varieties which differ in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar from each other and from the various standardised forms of Kurdish.

Classification

The Kurdish language and its dialects are part of the Northwestern Iranian languages group. The following macrodialects are commonly described for Kurdish although the debate continues whether some or indeed all of these should be classified as languages.

Kurdish dialects divide into three primaries groups:

I. Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish)

The branch with the most speakers, spoken in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Armenia and the Lebanon. It has an estimated 8-10 million speakers and has been written in the Latin alphabet since the 19030s. Its main dialects are:

Şengalî (Mosul),

Judikani (Central Anatolia)

Qerejdaxî (Urfa, Qamishlo etc)

Botanî (Boxtî) (Botan),

Serhedkî (Western Azerbaijan, Van, Erzurum, Kars, Ağrı, Muş usw.),

Hekkarî (Hakkari),

Behdînî (Dahuk and Western Azerbaijan)

Torî (Mardin and Siirt)

Xerzî (Batman and Siirt)

Qochanî (Chorasan)

Birjandî[1] (Chorasan)

Elburzî (Dailam)

Western Kurmanji (Marashkî) (Kahramanmaraş, Gaziantep, Sivas, Dersim, Adiyaman etc)

Central Kurmanji (around Diyarbakir)

II. Central Kurdish dialects group

Central Kurdish dialects group, also called Soraní, is the language of a plurality of Kurds in Eastern Kurdistan (Kurdistan in Iran) and Southern Kurdistan (Kurdistan in Iraq), with about 8 million speakers. Major subdialects of Central Kurdish dialects are

Mukrí,

Erdelaní,

Germíyaní,

Soraní,

Xushnaw,

Píjhder,

Píraní,

Wermawe, and

Hewlérí (or Soraní proper).

A line can be drawn to divide Soraní-speaking areas into a Persianized southeastern section and a more orthodox northwestern section, running from Bíjar to Kifrí, (See the map). The ergative con-struction in the Persianized Soraní has begun to disappear, while it is being retained in the non-Persianized northwestern section. Also, under the influence of Arabic and Neo-Aramaic languages, the northwest section of Soraní has acquired two fricative sounds (faucalized pharyngeal fricative 'ayn, and hâ), absent from other Kurdish, and in fact Indo-European languages.

Soraní is a recent labelling after the name of the former principality of Soran. In Silémaní, the Ottoman Empire had created a secundary school (Rushdíye), the graduates from which could go Istanbul to continue to study there. This allowed Soraní, which was spoken in Silémaní, to progressively replace Hewramí as the litterary vehicle. Mackenzie writes that the present Kurdish standard called Soranî is in fact a idealized version of the Silémaní dialect, which uses the phonemic system of the Píjhdar and Mukrí dialects. Objections have been made to th name Soraní on the grounds that the name of one dialect, Sonarí, spoken in the region Soran should not br extended to cover a group of dialect (E. M. Rasul, Núserí Kurd, No. 4, Nov. 1971).

Sources

III. Southern dialects group

the Southern Kurdish dialects group also called Pehlewaní or "Pahlawanik" group in some sources. The two other major branches of Kurdish language are, Dimílí[2] group also called "Zaza" and Hewramí group also called Goraní (Gúraní) in some sources. These are further divided into scores of dialects and sub-dialects as well, Please see KAL's Kurdish Genealogy Tree.

In far southern Kurdistan, both in Iraq and Iran, in an area from Shehreban to Dínewer, Hemedan, Kirmashan, and Xanekin, all the way to Mendelí, Pehle, Southern Kurdish Dialects group predominates. It is also the language of the populous Kakay tribe near Kerkúk and the Zengenes near Kifri. The Kurdish colony of western Baluchistan is also primarily Gurâni speaking. There are also poulous pockets of Southern Kurdish Dialects group found in the Alburz mountains (see map).

Southern Kurdish Dialects group and its dialects (Laki)[3] began their retreat in the 17th and 18th centuries and are now still under great pressure from Central Kurdish Dialects group speakers. With the avalanche of the Southern Kurdish refugees, nearly all speakers of Central Kurdish Dialects group, into eastern and southern Kurdistan (Kurdistan in Iran), the process of Southern Kurdish Dialects group dilution and assimilation has been hastened tremendously. Kirmashan, once the center of the Southern Kurdish Dialects group, is now a multi-lipgtial city, and very likely has a Central Kurdish Dialects group plurality.

The past expanse of Southern Kurdish Dialects group can still be detected in pockets of Gurâni-speaking farmers from the environs of Hekkarí in Turkey to Mosul (the Bajelans), and to Shehreban-Iess than forty miles northeast of Baghdad. Other major dialects of Souther Kurdish Dialects group, besides

Bajelaní, are

Kelhirí,

Guraní,

Nankilí,

Kendúley,

Senjabí,

Zengene,

Kakayí (or Dargazini), and

Kirmashaní.

Today, there are roughly 1.5 mil'lion Southern Kurdish Dialects speakers in Kurdistan.

Baba Tahir (ca. 1000-1060) of Hemedan is one of the very first poets in the East to write rubaiyats, the medium of Omar Khayyam’s fame. Baba Tahir’s rusticity and mastery of both Laki/Hewramí, Persian (and Arabic) have rendered his works unusually dear to the common people of both nations. His particular poetic meter is perhaps a legacy of the pre-Islamic poetic tradition of southeastern and central Kurdistan, or the celebrated "Pahlawiyât/Fahlawiyât," or more specific the "Awrânat" style of balladry. Many Yaresan religious works and Jilwa, the holy hymns of the Yezidi prophet Shaykh Adi, are also in this Pahlawiyât style of verse. Baba Tahir himself has now ascended to a high station in the indigenous Kurdish religion of Yaresanism as one of the avatars of the Universal Spirit.

The term Pehlewaní itself has clearly evolved from Pahlawand, i.e., that of "Pahla". Pahla comprised southern Kurdistan and northern Lurestan, perhaps the original home area of the language. The word Pahla is still preserved in corrupted from in the Kurdish tribal name Feylí[4] or "Pehlí", who incidentally still reside in southern Kurdistan, in the old Pahla region.

[1]Носителем этого курдского диалекта Birjandî был всемирно известный средновковый курдский астроном Абу-л-Вафа Мухаммад ал-Бузджани (940-998), уроженец Бузгана в Хорасане и автор "Книги Альмагеста" (Китаб ал-Мад-жисти) — обработки "Альмагеста" Птолемея, содержащую ревизию многих его положений, и "Объемлющего зиджа" (аз-Зидж аш-шамил). Абу-л-Вафа в Багдаде работал при дворе курдского правителей из династии Бувейхидов (Буидов)`Адуд ад-Даулы Фана-Хусрау (978-983) и его преемников.

[2]Dimilí dialects of Kurdish language

To the far north of Kurdistan along the upper courses of the Euphrates, Kizilirmaq, and Murat rivers in Turkey, the Dimilí branch of Kurdish language (less accurately but more commonly known as Zâza) is spoken by about 4.5 million (data from late 80's) Dimilí Kurds, (See the map). The larger cities of Darsim (now Tunçeli), Chapakhchur (now Bingol), and Siverek, and a large proportion of the Kurds of Bitlis, are Dimilí-speaking. There are also smaller pockets of this language spoken in various corners of Anatolia from Adiysman to Malatya (Melatye) and Maras (Meres), in Southern Kurdistan (northern Iraq, where the speakers are known as the Shebeks) and North Esatern Kurdistan (northwest Iran, the tribes of Dumbuli and some of the Zerzas) as well. The language seems in late classical and early medieval times to have been more or less spoken in all the area now covered by Northern Kurdish Dilects group in contiguous Kurdistan. Its domain also stretched west into Pontus, Cappadocia, and Cilicia, before a sustained period of assimilation and deportations obliterated the Kurdish presence in the area in the Byzantine period. The Dimilí further retreated from its former eastern domains to its present limited one under pressure from the advancing Northern Kurdish Dilects group speaking pastoralist Kurds. This loss of ground, which started at the beginning of the 16th century, continues to this day.

Dimilí is closely related to Hewramí (Hawramani, Ewramani), a relationship indicative of a time when a single form of Pahlawâni was spoken throughout much of Kurdistan, when after the late classical period, Kurdistan was homogenized through massive internal migrations. At that time the domain of the Pahlawâni language was uninterrupted across Kurdistan. The main bodies of Dimilí- and Hewramí-speaking Kurds are now at the extreme opposite ends of Kurdistan.

Major dialects of Dimilí are Sívirikí, Korí, Hezzú (or Hezo), Motkí (or Motí), and Dumbulí. The dialect of Galishí now spoken in the highlands of Gilan on the Caspian Sea may be a distant offshoot of Dimilí as well, brought here by the migrating medieval Daylamites from western and northern Kurdistan.

Dimilí has served as the prime language of the sacred scriptures of the Alevis, but not the exclusive one. Despite this, not much written material survives to give an indication of the older forms of Dimilí and its evolution. The documents come from rather unexpected sources: the early medieval Islamic histories. Ibn Isfandiyar in his history of Tabaristan, for example, preserves passages in the language of the Daylamite settlers of this Caspian Sea district, which resembles modern Dimilí.

[3]Laki (Lekí).

Laki, This vernacular is just a major dialect of Gurâni and is treated here separately not on linguistic grounds, but ethnological. The speakers of Laki have been steadily pulling away from the main body of Kurds, increasingly associating with their neighbouring ethnic group, the Lurs. The phenomenon is most visible among the educated Laks and the urbanites the countryside, the commoners still consider themselves Kurds in regions bordering other parts of Kurdistan, and Laks or Lurs where they border the Lurs. The process is a valuable living example of the dynamics through which the entire southern Zagros has been permanently lost by the Kurds since the late medieval period: an ethnic metamorphosis that converted the Lurs, Celus, Mamasanis, and Shabankdras into a new ethnic group (the greater Lurish ethnic group), independent of the Kurds.

Laki is presently spoken in the areas south of Hamadân and including the towns of Nahawand, Tuisirkân, Nurâbâd, Ilâm, Gelân, and Pahla (Pehle), as well as the countryside in the districts of Horru, Selasela, Silâkhur, and the northern Alishtar in western Iran. There are also major Laki colonies spread from Khurâsân to the Mediterranean Sea. Pockets of Laki speakers are found in Azerbaijan, the Alburz mountains, the Caspian coastal region, the Khurasani enclave (as far south as Birjand), the mountainous land between Qum and Kâshân, and the region between Adiyaman and the Ceyhan river in far western Kurdistan in Anatolia. There are also many Kurdish tribes named Lak who now speak other Kurdish dialects (or other languages altogether) and are found from Adana to central Anatolia in Turkey, in Daghistân in the Russian Caucasus, and from Ahar to the suburbs of Teheran in Iran.

The syntax and vocabulary of Laki have been profoundly altered by Luri, itself an offshoot of New Persian, a Southwest Iranic language. The basic grammar and verb systems of Laki are, like in all other Kurdish dialects, clearly Northwest Iranic. This relationship is further affirmed by remnants in Laki of the Kurdish grammatical hallmark, the ergative construction. The Laki language is therefore fundamentally different from Luri, and sin-iilar to Kurdish.

There are at least 1.5 million Laki speakers at present, and possibly many more, as they are often counted as Lurs.

[4]Pahli (Feylí).

The Pahli (Kurdish: Pehlí, پههلی also called Fayli or Faili) Kurds are an integral part of the Kurdish Nation, speaking the Laki dialect of Kurdish.

The roots of the Pahli (Fayli or Faili) Kurds go back to the Indo-European immigrants of the 1st millennium BC. The Pahlis are roughly equally divided between the followers of Shiite Islam and the native Kurdish religion of Yazdanism (the Ahl-i Haqq branch). Conversion into Shi'ite Islam among the Pahli Kurds began during the reign of the Safavid dynasty in Persia (1507-1721).

There are many folk stories and etymologies for the "meaning" of the name Pahli/Fayli/Faili. In his book, Mu'jam al-buldan, the geographer Yaqut of Hama notes in 13th century that the Pahli/Faili who reside the mountains separating Persia from Iraq are called Faili/Pahli because they are as huge as elephants (from "fil", Arabic for elephant)! Others proposed that the name was that of a ruler of the area, given later to his subjects. Some of these folkloric accounts are discussed by Khusrow Goran in his book Kurdistan Through Eyes "volume I (Stockholm, 1992).

The historical fact on the root of the name of the Pahli is fully clear. As M. R. Izady notes in his work (The Kurds: A Concise Handbook, London, 1992), the territory inhabited by the Pahli/Fayli Kurds was known as "Pahla" (meaning "Parthia") since the 3rd century AD. The area boasted to one of the most important Parthian settlements outside Parthia proper (or Khurasan). The name "Pahla" was likewise used for the area by the early Muslim geographer until the 13th century, after which the name "Luristan" gradually came to replace it. The Arabic texts recorded the name as "Fahla" or "Bahla", (Arabic lacks the letter "p"). From "Fahla" has since evolved Faila and Faili — the modern name of the Pahli Kurds. In fact, there is still a small town called Pahla in the south of the major city of Ilam in South Kurdistan which is the heart of traditional settlement occupied by Pahlis.

Geographical settlement

Since the ancient times the Pahli Kurds have lived in the Zagros Mountains in southern Kurdistan. They live on the two sides of the Kabir Koh mountain, forming the Iran-Iraq border.

The districts of southern Kurdistan inhabited by the Pahli/Faili Kurds, are as follow: Khanaqin, Qasri Shirin, Kirmanshah, Shahraban (now know as Al-Miqdadia), Kirind, Harunabad (former Shahabad, presently Islamabad), Sarpoli Zohab, Ilam , Gelan, Salihabad, Musian, Badra, Dihloran, Andimishk, Mandali, Zorbatiya, Jassan, Kut, and Azizyah in addition to a number of towns in the districts of Shaikh Sa’ad, Ali Sharqi, Ali Gharbi, and Kufah.

In the first decades of the 20th century, many Pahlis moved to Baghdad, giving rise to such urban names as the "Kurdish quarter," the "Kurdish alley," and the "Kurdish street" in Baghdad. Many were engaged as porters in that city.

The basic activity of the people on the border area is agriculture and sheep herding. Wheat, barley, vegetables and fruits are the main products. There are also some notable mineral resources in the area such as petroleum (at Naft Khana, Naft-Shahr and Dihloran) and natural gas (at Tanga Bijar).

In the northern areas, the Pahlis benefit from the waters of the Halwân (Alwand, Alwan) River which flows out from the Harunabad and Gelan regions, down toward Khanaqin, before joining the Diyala that flows into the Tigris. There are also many, springs, qanats and wells that help with irrigation and domestic water use. The climate is varied, ranging from semi-arid on the lowlands to the wet in the highlands. The mountains are usually covered with snow which melts in the summer to irrigate the lands below.

In summer many Pahlis move with their herds to the higher elevations to the vast grasslands, moving back to the lowlands during the winter time to their villages. In the towns and cities, many work in trade and the exchange of goods and other urban professions.

In the book Ameroir of Baghdad (Cyprus, El Rais Publishing House, 1993),the ex-minister Mosa Al-Shahbandar described the life of the Pahli Kurds.

The approximate population of the Pahli Kurds is about half a millions in Iraq, and one million in Iran.

References

Dr. A. Hassanpour, Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan 1918 — 1985, Mellen Research University Press, USA, 1992

Jemal Nebez, Toward a Unified Kurdish Language, NUKSE 1976

Prof. M. Izady, The Kurds, A Concise Handbook, Dep. of Near Easter Languages and Civilization Harvard University, USA, 1992.

http://www.kurdishacademy.org/?q=node/41

Курдские племена,кланы,роды.

Ж.С. Мусаэлян. Некоторые данные для характеристики курдов мангур и мамаш.

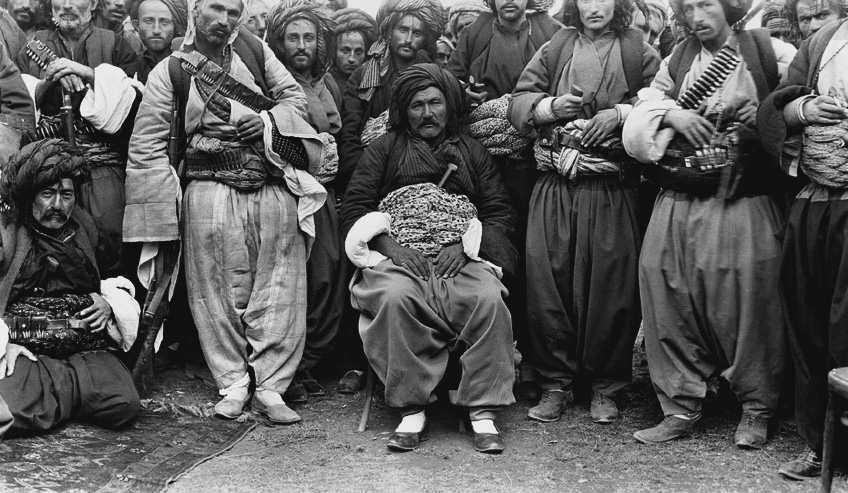

Байз «Ага», вождь клана «Шам» в курдском племени «Мангур», и его люди.

Эта фотография была сделана Александром Иясом 11 августа 1913 года в Тиркеше.

Ковровая картина-портрет Арианы Ханум, курдской дворянки, вероятно, мангурского происхождения, в традиционной одежде из Мукрияни

Курдские племена,кланы,роды.

Ж.С. Мусаэлян. Из истории курдского племени сенджаби(конец XVI — начало ХХ в.)

-

Новости6 лет назад

Новости6 лет назадТемур Джавоян продолжает приятно удивлять своих поклонников (Видео)

-

Страницы истории12 лет назад

Страницы истории12 лет назадО личности Дария I Великого и Оронта в курдской истории

-

История13 лет назад

История13 лет назадДуховные истоки курдской истории: АРДИНИ-МУСАСИР-РАВАНДУЗ

-

История14 лет назад

История14 лет назадКурдское государственное образования на территории Урарту: Страна Шура Митра

-

История15 лет назад

История15 лет назадДинастия Сасаниды и курды

-

Интервью6 лет назад

Интервью6 лет назадНациональная музыка для нашего народа — одна из приоритетных ценностей…

-

Культура6 лет назад

Культура6 лет назадТемур Джавоян со своим новым клипом «CÎnar canê («Дорогой сосед»)»

-

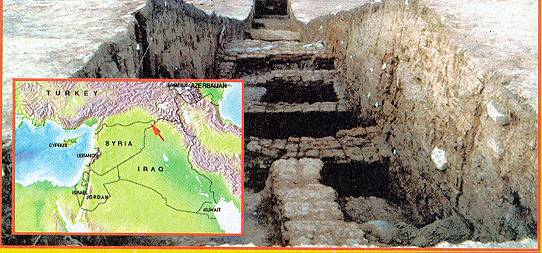

Археология16 лет назад

Археология16 лет назадКурдистан — колыбель цивилизации. Хамукар.

Вы должны войти в систему, чтобы оставить комментарий Вход